Your Protagonist Compass

What? No boat load of questions for today’s blog post? You mean I have to come up with something myself? Remember, I don’t make pirate ship floats, I didn’t just recently have a book accepted by Covenant, (although we are very close on my horror novel), and I know nothing about Canadian New Year. So you’ll have to blame yourselves if you don’t like today’s post..

Last week I was asked to do a workshop at LTUE. For those of you who haven’t been, it is an amazing writer’s conference primarily based around SciFi and Fantasy writing, and it’s really inexpensive. More info here. One of my more popular classes lately has been on creating a Character Bible. I’m teaching that at Storymakers with my awesome sister and fellow author Deanne Blackhurst, as well as at the UVU Teen Writers Conference in April. So it seemed like overkill to teach it again at LTUE. Instead I’ve been toying with the idea of creating a much more specific tool, I call a Protagonist Compass.

Here’s the basic concept. One of the biggest complaints I hear about books is that the main character is unbelievable. Janette Rallison had a great post about unbelievable teen romances on her blog. I think the biggest issue is that, while real people may be all over the board on what they do and why, readers expect more from a book. Books are not like real life. Our lives don’t have a clear plot line. We do have a start and we do have an end, but the rest of it is often more of a jumble than a progression. Books require much more precision. You can’t have a chapter where nothing happens, even if you do feel like you need it to connect two plot points. Each chapter must stand on its own.

It’s the same with characters. Readers may not realize it, but they want a clear understanding of what makes your protagonist tick. What drives her? What motivates her? If her motivations change, there needs to be a clear reason why. In order to do that, you need to understand where your protagonist is coming from and track where they are headed. In Scouts and in the Army, we used to go on a compass course. There were different points you had to locate by starting at one and using your compass to site in on the next. I think you could do something similar with a protagonist.

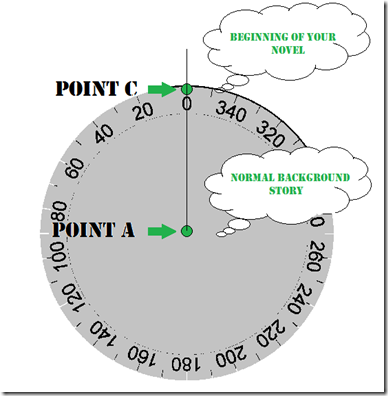

Let’s start with history. When your book starts, your character is at a certain point. Let’s call it point C. As you know from math classes, a point has no direction. It is simply a coordinate floating in space. Until you connect it with another point floating in space. Let’s call this point A. If you draw a line between point A and point C, you can track where your character should go. All things being equal, any decision they make should generally lead them to a point D along that line. Still with me? Let me give you an example.

In Demon Spawn, Blaze has grown up her whole life assuming certain things. Hell is just. Humans are sent to Hell for being evil, and have therefore earned any punishment they get. Her primary goal in life is to be successful in Hell. (i.e. get a good demon job, and continue the status quo.)

In our compass course, point A would be her normal demon spawn upbringing. Point C would be her first day of demon training—specifically her first day of meeting damned humans and sending them to their fates. Now you might ask, what about B? Or you might just figure that, like most authors, I’m either 1) Somewhat less than attentive to specific details, or 2) leaving a spot open for rewrites down the road.

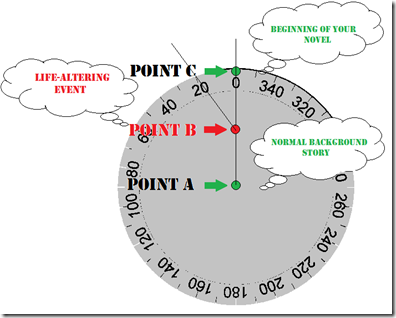

But no. There is a plan to my apparent lack of attention. Point B is left for a life altering experience that happened sometime in the protagonist’s life that changed its course significantly, but that occurred before the start of your story. For example:

Hopefully you’ve read Hunger Games. If not, go get a copy and read it. Some very good story-telling there. I won’t ruin too much of the story for you by saying that before the beginning of where the book starts, an event occurred in the life of Katniss—our protagonist. Let’s say that in Katniss’ life point A was being raised in a post-apocalyptic future where life was hard, children are sacrificed to a reality game every year, and her father teaches her how to hunt and gather wild plants and animals. Had life continued on its course, her biggest concerns would have been those of any teen in her town. Avoiding the games, making a living, meeting a guy, etc.

But when she was younger, a major event shook her life. Her father died. That would have been a traumatic event for any child. But to make matters worse, her mother had a total breakdown, leaving Katniss to feed the family or let them all starve. This event so scarred her that now the biggest motivating factor in her life is protecting her family—especially her little sister, Prim. This is point B.

If we look at our compass course, we can see that this single event altered the course of her life. Any decisions she makes after this point will be affected by this event. Should anything threaten this direction, it will immediately create conflict. The more it threatens to alter this course, the bigger the conflict will be. Now remember that point A has not gone away. She still does not want to be part of the games. And she is somewhat attracted to a guy. But even the guy she is attracted to comes more as a result of a desire to provide for her family than a physical attraction. And she has taken a greater risk of being chosen for the games purely to provide for her family. So it is clear that while point A still exists, point B overrides it.

One of the interesting things about Katniss’ life changing event is that we don’t learn about it until after point D, which I’ll get to in a moment. Many authors would be tempted to either begin the book with a prologue where we see what happened to her father and how her mother reacted. Or they would show a flashback prior to point C, so the reader would understand clearly why Katniss makes the decision she does. This is not necessary. You actually have two better options. One is implied history. For example, if an eighth grader’s first reaction to his new school is that he will fit inside the lockers, we can surmise that he has been stuck in a locker before. It is implied that not only has he been picked on, but that he expects to be at his new school as well.

Another method is through actions. Collins actually uses both methods. We learn that Katniss’ father made the bows she is using and that he is no longer in her life. We also see her out hunting to provide food for her family. We don’t know all the details yet, but we “get” that Katniss is about protecting her family in her father’s absence.

Knowing points A and B, it is pretty easy to surmise point D. (Spoiler alert) Point D must be a decision where points A and B come into direct conflict, and that once more changes the course of Katniss’ life. And sure enough it is. Katniss doesn’t want to be chosen for the games. She isn’t. But Prim is. Now, had Katniss’ father not died, we don’t know for sure what Katniss would have reacted to this event. But knowing that her desire to protect her younger sister is more important than anything, it is clear what she must do. Point B overrides point A, and she takes Prim’s place. This is perfectly consistent with Katniss’ prime motivation.

Once her decision is made, we get the back story. And along with it, another key point on our compass course. One that also took place before the story begins. Let’s call this point B2. When Katniss was near to dying—and failing her family, a boy tossed her a loaf of bread, causing himself suffering. Katniss hasn’t thought about this a lot over the years. B1 is clearly not as strong as B. But it suddenly becomes an issue when that very boy is chosen to go to the games as well. He may very well have saved her life. And she definitely owes him. But only one of them can survive the games, and her prime motivation is still providing for her family—which can only occur if she survives, meaning the boy who saved her life must die.

What the casual reader sees is that almost immediately Katniss and Peeta begin to argue. Like many romances, it seems impossible that they can ever get together. What they make not actively think about is that this back and forth arguing—occasionally broken up by moments of friendship or even actual tension—only work because the correct motivating factors were put in place first. If Peeta had not saved Katniss’ life we wouldn’t buy the romance, at least on her part. If he didn’t already love her, we wouldn’t buy the self-sacrificing behavior on his part. If Katniss’ prime motivation wasn’t saving her sister, we would hate her for being such a jerk to him.

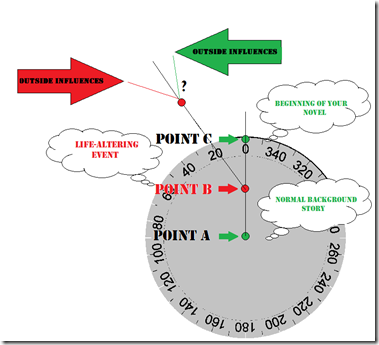

Occasionally, Katniss can be pulled off track. She can start to fall for Peeta, or decide to help out another person in the game. But protecting her family must come first. Unless outside circumstances change. Sensing the romantic tension, we hope and expect that Katniss and Peeta will get together. (Even though this is not a traditional romance.) But no matter how much we might want it, we will not accept it unless there is a major event that is strong enough to alter the course set in place by point B. These outside influences must be strong enough to alter the protagonist’s course. They must be believable and to some extent the reader must be prepared to receive them.

Of course if you’ve read the book, what know what Peeta did in order to change things. Had that not occurred, readers would have been unhappy with the major decision Katniss makes near the end of the book. They might not have known why they were unhappy with it—especially since they wanted it to happen all along. They just would have said it was unbelievable.

Going briefly back to Demon Spawn, the life altering event doesn’t always happen before point C where the story starts. Blaze’s point B takes place shortly after the story begins, when she discovers a young human girl has been sent to Hell. This event doesn’t have an immediate impact on Blaze, but it opens her up to outside influences. In the story, she has two outside influencers tugging at her. Cinder, her roommate, is all about immediate gratification—mostly in the form of guys. Onyx, her best male friend, believes in change and questioning authority. These two outside influencers have various amounts of success, but ultimately which one wins out is the result of the events Blaze experiences herself.

Had she not seen the human child and questioned what the girl could possibly done to be sent to hell, she might not have been open to Onyx’s influences in the way she eventually is.

Hopefully you get the general idea here. Each major decision in your protagonist’s story must be checked against the compass of his past decisions. If you want the girl and the guy to get together, you must either give them back stories that lead to this, or create strong enough outside influences to swing the compass one way or another. If you know your main character will finish the story with a different view of life than they began it with, you must create believable events to shape that change, or your readers will not believe it when it finally happens.

For more detailed examples and some hands on class work, come to my workshop at LTUE.

P.S. If you are interested in LDS fiction, you have a great new column to follow by Andrew Hall called This Week in Mormon Literature. I've followed him fro years and he does some amazing research. And I don't just say that because he called the Frog Blog one of, "the best LDS literature discussion blogs."

9 Comments:

Really insightful. This breakdown is genius. As I read I kept applying the compass to the mc in my current wip, and the antagonist as well. Good stuff again, Jeff!

Without fail, Jeff, every time I talk to you or read your posts my perspective changes or I learn at least 10 new things (which makes this post point U or V on my writing compass- ha ha.) I feel like I just attended a class at LDStorymakers. Thank you for never missing an opportunity to teach us something.

You rock. Seriously.

Shanda :)

I was never strong on the compass course. I guess I'd better start practicing.

Do you plot your characters that precisely or do you have a natural sense for yor characters arc? In other words do you plot yor course or do you analyze the strength of the character with the compass?

Holy cheese crackers, Jeff. This. Is. Awesome. I am absolutely going to this class at LTUE.

Great stuff J. Savage. You're wonderful. And kind. And stop wasting your time helping us so you can write another book. Okay?

I was told, by an excellent author, Arthur Bishop, a similar thing, but he didn't use point A, B, C, or even D. And there was no compass in his bag of technical writing tricks. Is it fair to compare what he told me with what you're saying?

Mr. Bishop told me never (yes, he said never) begin a story with backstory. The opening chapters shouldn't contain any backstory. Get your story going in the present. Then, if there is backstory that needs to be told, tell it somewhere after the one third to halfpoint in your novel, and limit it to the essential backstory that will further your present story and deepen the readers relationship with the characters. If you share backstory that does nothing more than psychoanalyze your characters, the backstory is worthless. But if it answers the question: Why is the character behaving they way they are? Or if it has information that will alter the course of the story, then the backstory is relevant.

The other bit of related advice he gave me was: backstory may be very important for the author to know. But it may not be relevant for the reader to know. The backstory that the author needs to know allows you to build the image, tendencies, quirks, preferences, characterizing actions (she blew her nose on the pillow case), dress, grooming, status in life, job position, relative income, relationships between family and friends which are essential for making your character who they are. BUT YOU DO NOT NEED TO SHARE IT WITH THE READER. The reader will get to know your character like you get to know people in real life--one event at a time, one snippet of dialouge at a time, one adventure scene at a time, or one romantic scene at a time. And that's a much more unfolding, enjoyable way to met a character. If you dump all that backstory CHARACTER development stuff in one large chunk up front, you run the risk of drawing your character into a box from which she may never emerge. And that throws any unpredictability your character may have hidden deep inside of them (the fun discovery elemnts of character) out the window.

Backstory can kill your character. Backstory can kill your story.

I can't tell you how many novels I've read where, even in the opening paragraphs (to say nothing of the opening chapters) the author works feverishly to hide the fact that she's sharing backstory disguised as character musings, observations, and perspectives. In other words, the author really believes they are developing character when what they're actually sharing is backstory.

Thanks all! Sara, you butter churn, we totally need to hang out at LTUE.

Anon, I agree completely with you and Mr. Bishop. Back story is "back" for a reason. It should not be part of your story unless it is vital for the reader to know. Which, in the case of Hunger Games, it very clearly was. The longer you can stay in the here and now, the better. You build up credibility with the reader.

The biggest mistake I see with new authors is trying to give the reader a whole bunch of info before actually beginning the story. It's like starting a movie with the credits.

There are a few exceptions, but they are quite rare.

However, you as the author MUST know the back story or you have no understanding of what drives and motivates your character.

Steve,

At this point in my writing, having completed ten novels, a lot of this is just second nature. For example, when I wrote Demon Spawn, I knew what was going to set everything off, how it would change Blaze, and where she would end up.

At the same time, I do question the motivations of my characters all the time. For example, in the second 4th Nephite book, I need the protag's best friend to go back in time with him. But it would be totally unbelievable to have the friend go willingly unless there was a major motivation. In this case, he is demanding to know what changed Kaleo's views so radically. It's a secret he is determined to learn.

So a lot of the tools I create, like the compass, are trying to clarify what I do when I plan a story.

Jeff, You are so dang brilliant. Thanks for sharing all those brains with the rest of us.

Oh great master, I bow at your awesomeness!! Wow! I agree with Shanda, I feel like I just sat in a class at writers conference but for FREE!!!

This post is very important to me right now. I have been playing around with some backstory (in my WIP) and not sure where to include it. This really helped me see what I needed to do instead. I keep asking, when are you going to write a "writing" book to educate all of us and really get paid for doing it? Thanks for sharing so much of your great wisdom and experience.

Post a Comment

<< Home